Last Updated: July 19, 2023

Medically reviewed by NKF Patient Education Team

About albuminuria (proteinuria)

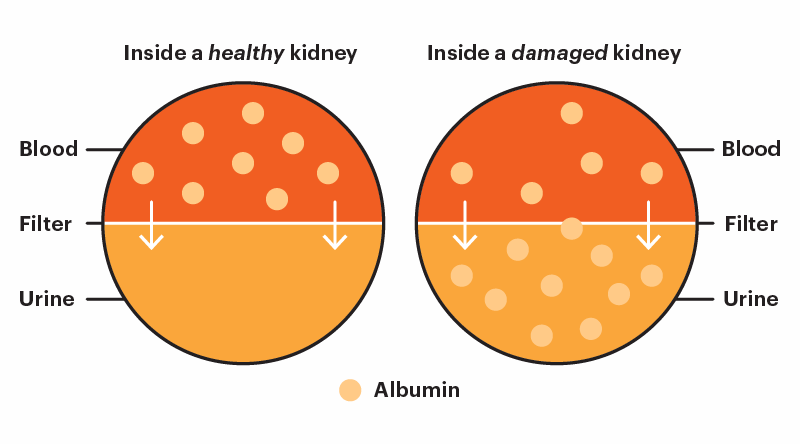

Albuminuria (sometimes referred to as proteinuria) is when you have albumin in your urine. Albumin is an important protein normally found in the blood that serves many roles in the body - building muscle, repairing tissue, and fighting infection. It is not usually found in the urine.

Healthy kidneys stop most of your albumin from getting through their filters and entering the urine. There should be very little or no albumin in your urine. If your kidneys are damaged, albumin can “leak” through their filters and into your urine.

Albuminuria (proteinuria) is not a separate disease. It is a symptom of many different types of kidney disease and a significant risk factor for complications. Having albumin in your urine can be a sign of kidney disease, even if your estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is above 60 or “normal”.

Albuminuria (proteinuria) is not a separate disease. It is a symptom of many different types of kidney disease and a significant risk factor for complications.

Signs and symptoms

Most people with albuminuria (proteinuria) may not notice any symptoms. This is why it is so important to get regular health checkups (including lab tests), especially if you have any risk factors for albuminuria or kidney disease.

If symptoms are present, you may notice one or more of the following:

- Foamy urine

- Puffiness around the eyes (especially in the morning)

- Frequent urination (peeing more often than usual)

- Swelling of your feet, ankles, belly area, or face

One day, no one’s life will be lost to kidney disease.

- Equip patients and families with knowledge, resources, and access to high-quality care.

- Advocate for policies that address disparities and prioritize kidney health for all.

- Fund research and technology to advance early detection, improve treatment, and expand transplant access.

Causes

Albuminuria (proteinuria) is caused by kidney damage, specifically when the damage occurs in the glomerulus (the kidney’s filter). Sometimes this is temporary (short-term damage), while other times it is chronic (long-term damage). The exact cause for the kidney damage is different for each person and may even be due to several factors combined.

Some of the most common causes of temporary (short-term) albuminuria include:

- Dehydration (not drinking enough water)

- High-intensity exercise

- Fever and/or infection

- Heart failure exacerbation (flare-up)

Some of the most common causes of chronic (long-term) albuminuria include:

- Diabetes (especially if your blood sugars are higher than your target range)

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Heart disease and/or heart failure

- Glomerular disease (such as IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), or glomerulonephritis)

Having albuminuria may not always mean you have actual kidney damage. This is why repeat testing is so important – to help tell the difference between chronic (long-term) kidney damage and temporary (short-term) stress on the kidneys.

Having albuminuria may not always mean you have actual kidney damage. This is why repeat testing is so important – to help tell the difference between chronic (long-term) kidney damage and temporary (short-term) stress on the kidneys.

Types

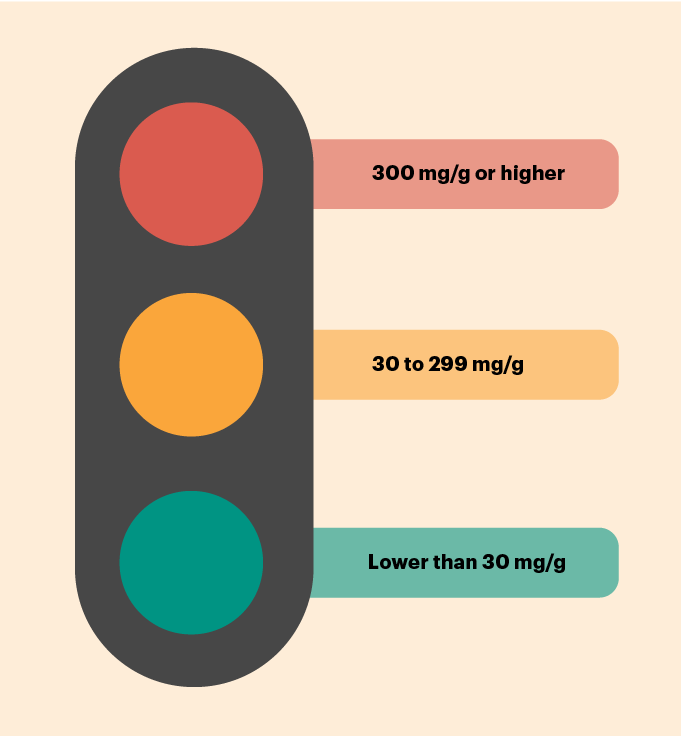

You may have heard or read about the words “microalbuminuria” and “macroalbuminuria”. These words were used in the past to help describe categories for how high a person’s urine albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR) level is. However, these separate words are no longer recommended - they add confusion without providing any extra benefit. Newer research has shown that any uACR level above the goal range is a risk factor for complications. Any level above 30 mg/g is now called “albuminuria” (instead of using two separate terms).

Complications

Albuminuria is a significant risk factor for developing complications. Some of these complications include:

- Kidney failure

- Cardiovascular disease (heart failure, heart attack, or stroke)

- Heart failure

- Decreased life expectancy (early death)

Your risk for getting these complications is directly connected with your uACR level. This means a higher uACR level comes with a higher risk for developing one or more of these complications. Getting your uACR level down will help lower your risk for complications, even if you are not able to get your uACR level into the goal range.

Diagnosis

Urine albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR)

The primary way to diagnose albuminuria is through a urine test called the urine albumin-creatinine ratio (uACR). Your uACR results help describe the degree of albuminuria you may be experiencing, if any.

A lower number is better for this test, ideally lower than 30. A value of 30 or higher suggests you may be at a higher risk for complications. The higher your number, the higher your risk.

The quantitative uACR test is the most preferred initial test for adults at high risk for kidney disease because it offers the most precision while also being convenient. The National Kidney Foundation supports semi-quantitative uACR testing for adults at increased risk for kidney disease when access to quantitative testing is limited. Semi-quantitative tests offer less precision but more convenience since they can be done at home or in a doctor’s office. A positive result on a semi-quantitative test should be confirmed with a quantitative test.

It is important to emphasize that this test often needs to be repeated one or more times to confirm the results. Decisions are rarely made based on the results of one test.

Other tests

If your uACR is much higher than the target range, extra tests may be recommended to get more information about what may be causing your albuminuria. These tests may include:

- Kidney biopsy - especially if there is a concern for glomerular disease. This test can help find out what caused your kidney disease and how much damage to the kidneys has already happened.

- Imaging tests - especially if there is a concern for kidney cancer, kidney stones, or structural problems within the kidney. These tests include things like an ultrasound or CT scan. These produce a picture of your kidneys and urinary tract.

Treatment

Overview

The main goal of treatment is to lower your overall risk for developing complications. This starts with addressing the most likely cause for your albuminuria (proteinuria). For most people, the initial focus will likely be on getting your blood pressure and/or blood sugar levels into their target ranges. A combination of lifestyle modifications and medication is generally the most effective approach for treating albuminuria and lowering your risk for complications.

The main goal of treatment is to lower your overall risk for developing complications, starting with targeting the most likely cause for your albuminuria.

Medications

Medications that help you manage your high blood pressure and/or diabetes (if applicable) are usually the first step. Medications that work directly in the kidneys to help decrease the amount of pressure placed on your glomeruli (the filters in your kidney) are also usually recommended. These medications are commonly known as “kidney protective” because they can help keep your glomeruli (filters in your kidneys) healthy and lower uACR levels.

Nutrition

Ask your kidney dietitian, diabetes care & education specialist, or healthcare provider about your nutritional needs. Fortunately, the steps you may already be taking to help manage any other health conditions you may have (high blood pressure, diabetes, heart failure) can help with albuminuria too.

For general guidance on nutrition, click the link that best matches your situation:

- Nutrition for people with stage 1-4 kidney disease

- Nutrition and kidney failure

- Nutrition for children with chronic kidney disease

Exercise

Regular exercise is important for a healthy lifestyle. For general guidance on exercise recommendations, visit the Staying fit with kidney disease page.

Other steps

Some additional steps that can help you lower your uACR levels and lower your risk for a cardiovascular event (heart attack or stroke) include (not all recommendations will apply to everybody):

- Stop smoking and/or using tobacco products.

- Work toward losing extra weight through a balanced diet and physical activity.

- Limit how much alcohol you drink.

Questions to Ask

- When was the last time I had a uACR test?

- What were the results of my last uACR test?

- What steps can I take today to lower my uACR level into the goal range and lower my risk of complications?

- What are my other risk factors for having a cardiovascular event in the future?

- What actions can I take today to improve my kidney health and decrease my cardiovascular risk?